Staggered Difference-in-Differences#

This notebook demonstrates the StaggeredDifferenceInDifferences estimator in CausalPy, which handles staggered adoption settings where different units receive treatment at different times.

The Staggered Adoption Problem#

In many real-world settings, treatment is not applied to all units at the same time. Instead, different cohorts of units adopt treatment at different times. This creates a “staggered adoption” pattern.

Why Standard Two-Way Fixed Effects (TWFE) Can Fail#

The standard TWFE regression with a single treatment indicator:

can produce biased estimates in staggered settings [Goodman-Bacon, 2021] because:

Already-treated units serve as implicit controls for later-treated units

The estimate is a weighted average of treatment effects that can include negative weights

Dynamic treatment effects (effects that vary over time since treatment) are not properly accounted for

Note

Notice that \(\tau\) in the TWFE formulation above is a scalar—a single number meant to summarize the treatment effect across all units and time periods. This is a fundamental limitation: it assumes the treatment effect is constant, regardless of when a unit was treated or how long they’ve been treated.

Event-study and modern staggered DiD approaches address this by treating treatment effects as dynamic—allowing \(\tau\) to vary by event-time (time relative to treatment). This captures realistic patterns like effects that build up over time, decay, or differ across treatment cohorts.

The Imputation-Based Solution#

CausalPy’s StaggeredDifferenceInDifferences uses an imputation-based approach inspired by Borusyak et al. [2024]:

Fit a model on untreated observations only - using pre-treatment periods for eventually-treated units plus all periods for never-treated units

Predict counterfactual outcomes for all observations

Compute treatment effects as the difference between observed and predicted outcomes

Aggregate effects by event-time (time relative to treatment) for an event-study curve

import warnings

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import causalpy as cp

from causalpy.data.simulate_data import generate_staggered_did_data

warnings.filterwarnings("ignore", category=FutureWarning)

%load_ext autoreload

%autoreload 2

%config InlineBackend.figure_format = 'retina'

Generate Synthetic Staggered Panel Data#

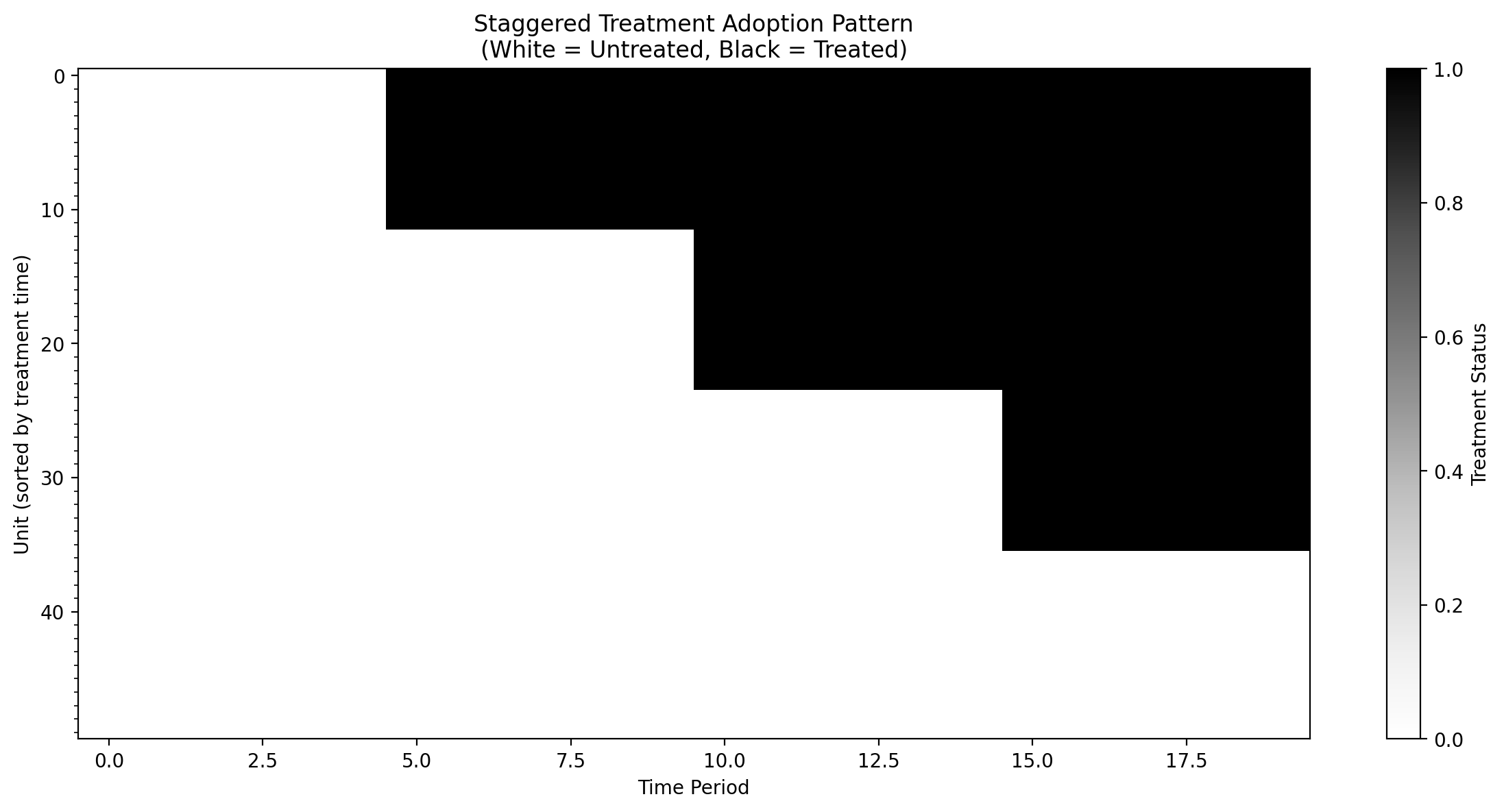

We’ll create synthetic data with:

50 units observed over 20 time periods

3 treatment cohorts adopting at times 5, 10, and 15

Some never-treated units

A known dynamic treatment effect that we can verify

# Define the true treatment effects (dynamic effects that ramp up then stabilize)

# This is used both for data generation and for validating our estimates

TRUE_EFFECTS = {0: 1.0, 1: 1.5, 2: 2.0, 3: 2.5}

# Generate synthetic data with known treatment effects

df = generate_staggered_did_data(

n_units=50,

n_time_periods=20,

treatment_cohorts={5: 12, 10: 12, 15: 12}, # 3 cohorts, 14 never-treated

treatment_effects=TRUE_EFFECTS,

unit_fe_scale=2.0,

time_fe_scale=1.0,

sigma=0.3,

seed=42,

)

df.head()

| unit | time | treated | treatment_time | y | y0 | tau | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 15.0 | 0.618468 | 0.898554 | 0.0 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 15.0 | 1.179091 | 1.240722 | 0.0 |

| 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 15.0 | -1.132728 | -0.847722 | 0.0 |

| 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 15.0 | 0.188053 | 0.289763 | 0.0 |

| 4 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 15.0 | 0.391154 | 0.139062 | 0.0 |

Show code cell source

print(

f"Panel dimensions: {df['unit'].nunique()} units × {df['time'].nunique()} periods"

)

print(f"Total observations: {len(df)}")

print(f"\nTreatment cohorts:")

print(df.groupby("treatment_time")["unit"].nunique())

Panel dimensions: 50 units × 20 periods

Total observations: 1000

Treatment cohorts:

treatment_time

5.0 12

10.0 12

15.0 12

inf 14

Name: unit, dtype: int64

Visualize the Staggered Treatment Pattern#

Show code cell source

# Create a heatmap of treatment status

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(12, 6))

# Pivot to get unit x time matrix of treatment status

treatment_matrix = df.pivot(index="unit", columns="time", values="treated")

# Sort by treatment time for better visualization

unit_treatment_times = df.groupby("unit")["treatment_time"].first().sort_values()

treatment_matrix = treatment_matrix.loc[unit_treatment_times.index]

im = ax.imshow(

treatment_matrix.values,

aspect="auto",

cmap="Greys",

interpolation="nearest",

vmin=0,

vmax=1,

)

ax.set_xlabel("Time Period")

ax.set_ylabel("Unit (sorted by treatment time)")

ax.set_title(

"Staggered Treatment Adoption Pattern\n(White = Untreated, Black = Treated)"

)

from matplotlib.ticker import MultipleLocator

ax.yaxis.set_minor_locator(MultipleLocator(1))

plt.colorbar(im, ax=ax, label="Treatment Status")

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Fit the Staggered DiD Model#

We’ll use a model with unit and time fixed effects, which is the baseline counterfactual model for imputation.

The formula defines a model of untreated potential outcomes. Crucially, this model is fitted only on observations that are not yet treated: pre-treatment periods for units that eventually receive treatment, plus all periods for never-treated units. The fitted model is then used to predict what the treated units would have experienced in the absence of treatment (the counterfactual). Treatment effects are computed as the difference between observed outcomes and these counterfactual predictions.

The formula y ~ 1 + C(unit) + C(time) specifies a two-way fixed effects model, but you’re not limited to this specification. If you have additional covariates that help explain variation in the outcome—such as weather conditions, seasonality indicators, economic indicators, or any other time-varying controls—you can include them in the formula. For example, y ~ 1 + C(unit) + C(time) + temperature + holiday would add temperature and holiday effects to the model. Including relevant covariates can improve the precision of your treatment effect estimates and strengthen the plausibility of the parallel trends assumption.

# Fit the staggered DiD model with PyMC

result = cp.StaggeredDifferenceInDifferences(

df,

formula="y ~ 1 + C(unit) + C(time)",

unit_variable_name="unit",

time_variable_name="time",

treated_variable_name="treated",

treatment_time_variable_name="treatment_time",

model=cp.pymc_models.LinearRegression(

sample_kwargs={

"progressbar": True,

"random_seed": 42,

}

),

)

Initializing NUTS using jitter+adapt_diag...

Multiprocess sampling (4 chains in 4 jobs)

NUTS: [beta, y_hat_sigma]

Sampling 4 chains for 1_000 tune and 1_000 draw iterations (4_000 + 4_000 draws total) took 2 seconds.

The rhat statistic is larger than 1.01 for some parameters. This indicates problems during sampling. See https://arxiv.org/abs/1903.08008 for details

The effective sample size per chain is smaller than 100 for some parameters. A higher number is needed for reliable rhat and ess computation. See https://arxiv.org/abs/1903.08008 for details

Sampling: [beta, y_hat, y_hat_sigma]

Sampling: [y_hat]

Sampling: [y_hat]

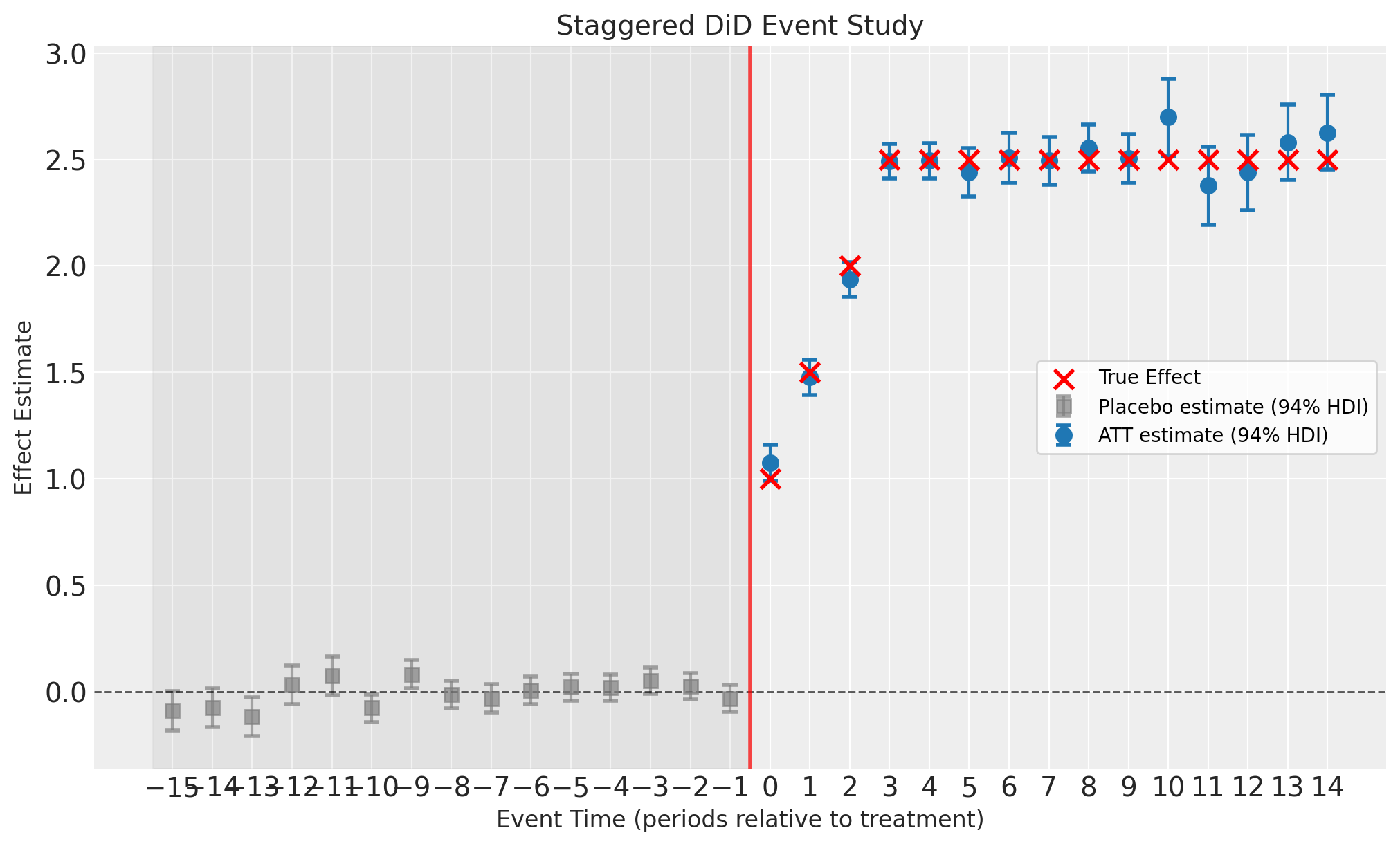

Event-Study Plot#

The event-study plot shows estimates at each event-time (time relative to treatment). Key features:

Pre-treatment placebo estimates (event-time < 0, gray squares): These should be close to zero if the parallel trends assumption holds. They are computed as residuals (observed minus predicted) for eventually-treated units before they receive treatment. These are not treatment effects—they are fit diagnostics.

Post-treatment ATT estimates (event-time ≥ 0, blue circles): These are the actual Average Treatment effect on the Treated (ATT) estimates showing the dynamic treatment effect over time since treatment.

Error bars: 94% Highest Density Intervals (HDI) from the Bayesian posterior

Gray shaded region: Pre-treatment period (placebo check zone)

Note

Since we generated synthetic data with known treatment effects, we can overlay the true effects on the plot to validate the estimator’s performance. In real applications, the true effects are unknown.

fig, ax = result.plot()

# Overlay true treatment effects (only possible because we simulated the data)

att_et = result.att_event_time_

post_treatment = att_et[att_et["event_time"] >= 0]

true_vals = [TRUE_EFFECTS.get(e, 2.5) for e in post_treatment["event_time"]]

ax[0].scatter(

post_treatment["event_time"],

true_vals,

color="red",

marker="x",

s=100,

linewidths=2,

zorder=5,

label="True Effect",

)

ax[0].legend()

plt.show()

View Summary Statistics#

The n_obs column in the event-time ATT table shows the number of treated unit-time observations contributing to each event-time estimate. This varies across event-times because different cohorts have different lengths of post-treatment history. For example, units treated early in the panel contribute observations at all event-times, while units treated later only contribute to earlier event-times (e.g., event-time 0, 1, 2) before the panel ends.

result.summary(round_to=2)

======================Staggered Difference in Differences=======================

Formula: y ~ 1 + C(unit) + C(time)

Number of units: 50

Number of time periods: 20

Treatment cohorts: [np.float64(5.0), np.float64(10.0), np.float64(15.0)]

Never-treated units: 14

Event-time estimates:

event_time type att att_lower att_upper n_obs

-15 placebo -0.089727 -0.182651 0.001678 12

-14 placebo -0.076510 -0.165531 0.015464 12

-13 placebo -0.117002 -0.208039 -0.026421 12

-12 placebo 0.030745 -0.059782 0.121330 12

-11 placebo 0.074539 -0.016959 0.164344 12

-10 placebo -0.076136 -0.143237 -0.012652 24

-9 placebo 0.081386 0.014587 0.148938 24

-8 placebo -0.013679 -0.080336 0.051946 24

-7 placebo -0.032442 -0.098791 0.033575 24

-6 placebo 0.004729 -0.060527 0.071197 24

-5 placebo 0.021254 -0.042810 0.082547 36

-4 placebo 0.018158 -0.044094 0.081336 36

-3 placebo 0.051156 -0.011460 0.112558 36

-2 placebo 0.024409 -0.037726 0.085558 36

-1 placebo -0.033889 -0.096769 0.030393 36

0 ATT 1.074842 0.990362 1.159714 36

1 ATT 1.477406 1.395102 1.559364 36

2 ATT 1.936514 1.854290 2.016924 36

3 ATT 2.491325 2.412439 2.572188 36

4 ATT 2.494277 2.412555 2.577045 36

5 ATT 2.439444 2.327826 2.554720 24

6 ATT 2.508034 2.391311 2.625448 24

7 ATT 2.495111 2.382095 2.607191 24

8 ATT 2.554547 2.444958 2.666289 24

9 ATT 2.504438 2.390342 2.620304 24

10 ATT 2.699058 2.515626 2.879858 12

11 ATT 2.379267 2.192838 2.562129 12

12 ATT 2.441211 2.260847 2.617471 12

13 ATT 2.580254 2.405220 2.759980 12

14 ATT 2.625220 2.452779 2.803349 12

Model coefficients:

Model coefficients:

Intercept 0.78, 94% HDI [0.63, 0.95]

C(unit)[T.1] -2.6, 94% HDI [-2.9, -2.3]

C(unit)[T.2] 0.92, 94% HDI [0.62, 1.2]

C(unit)[T.3] 1.4, 94% HDI [1.2, 1.6]

C(unit)[T.4] -4.4, 94% HDI [-4.6, -4.2]

C(unit)[T.5] -3.2, 94% HDI [-3.4, -3]

C(unit)[T.6] -0.37, 94% HDI [-0.58, -0.18]

C(unit)[T.7] -1.1, 94% HDI [-1.3, -0.94]

C(unit)[T.8] -0.43, 94% HDI [-0.73, -0.13]

C(unit)[T.9] -2.3, 94% HDI [-2.6, -2.1]

C(unit)[T.10] 1.4, 94% HDI [1.2, 1.5]

C(unit)[T.11] 1, 94% HDI [0.73, 1.3]

C(unit)[T.12] -0.37, 94% HDI [-0.58, -0.18]

C(unit)[T.13] 1.8, 94% HDI [1.6, 2]

C(unit)[T.14] 0.34, 94% HDI [0.12, 0.54]

C(unit)[T.15] -2.3, 94% HDI [-2.6, -2.1]

C(unit)[T.16] 0.21, 94% HDI [-0.088, 0.51]

C(unit)[T.17] -2.4, 94% HDI [-2.6, -2.2]

C(unit)[T.18] 1.2, 94% HDI [0.99, 1.5]

C(unit)[T.19] -0.7, 94% HDI [-0.89, -0.5]

C(unit)[T.20] -0.9, 94% HDI [-1.1, -0.7]

C(unit)[T.21] -1.7, 94% HDI [-2, -1.4]

C(unit)[T.22] 2, 94% HDI [1.8, 2.2]

C(unit)[T.23] -0.9, 94% HDI [-1.1, -0.72]

C(unit)[T.24] -1.3, 94% HDI [-1.6, -1.1]

C(unit)[T.25] -1.3, 94% HDI [-1.6, -0.95]

C(unit)[T.26] 0.51, 94% HDI [0.27, 0.74]

C(unit)[T.27] 0.18, 94% HDI [-0.021, 0.37]

C(unit)[T.28] 0.23, 94% HDI [0.015, 0.43]

C(unit)[T.29] 0.18, 94% HDI [-0.025, 0.39]

C(unit)[T.30] 3.7, 94% HDI [3.5, 4]

C(unit)[T.31] -1.3, 94% HDI [-1.6, -1.1]

C(unit)[T.32] -1.4, 94% HDI [-1.6, -1.2]

C(unit)[T.33] -2.1, 94% HDI [-2.3, -1.9]

C(unit)[T.34] 0.65, 94% HDI [0.35, 0.96]

C(unit)[T.35] 1.8, 94% HDI [1.5, 2.1]

C(unit)[T.36] -0.81, 94% HDI [-1, -0.61]

C(unit)[T.37] -2.1, 94% HDI [-2.3, -1.8]

C(unit)[T.38] -2.3, 94% HDI [-2.5, -2.1]

C(unit)[T.39] 0.68, 94% HDI [0.48, 0.87]

C(unit)[T.40] 0.91, 94% HDI [0.66, 1.1]

C(unit)[T.41] 0.7, 94% HDI [0.47, 0.93]

C(unit)[T.42] -2.1, 94% HDI [-2.3, -1.9]

C(unit)[T.43] -0.16, 94% HDI [-0.37, 0.045]

C(unit)[T.44] -0.2, 94% HDI [-0.41, 0.0086]

C(unit)[T.45] -0.0012, 94% HDI [-0.29, 0.28]

C(unit)[T.46] 1.1, 94% HDI [0.91, 1.4]

C(unit)[T.47] -0.23, 94% HDI [-0.52, 0.066]

C(unit)[T.48] 0.81, 94% HDI [0.59, 1]

C(unit)[T.49] -0.54, 94% HDI [-0.84, -0.25]

C(time)[T.1] 0.38, 94% HDI [0.26, 0.49]

C(time)[T.2] -1.7, 94% HDI [-1.8, -1.6]

C(time)[T.3] -0.56, 94% HDI [-0.68, -0.44]

C(time)[T.4] -0.77, 94% HDI [-0.89, -0.66]

C(time)[T.5] -0.96, 94% HDI [-1.1, -0.84]

C(time)[T.6] -0.51, 94% HDI [-0.64, -0.38]

C(time)[T.7] 1.3, 94% HDI [1.2, 1.4]

C(time)[T.8] -1, 94% HDI [-1.1, -0.89]

C(time)[T.9] 0.72, 94% HDI [0.59, 0.84]

C(time)[T.10] -1.9, 94% HDI [-2.1, -1.8]

C(time)[T.11] -0.55, 94% HDI [-0.7, -0.42]

C(time)[T.12] -0.028, 94% HDI [-0.17, 0.11]

C(time)[T.13] 0.38, 94% HDI [0.24, 0.53]

C(time)[T.14] 0.51, 94% HDI [0.37, 0.65]

C(time)[T.15] 0.45, 94% HDI [0.28, 0.63]

C(time)[T.16] -0.61, 94% HDI [-0.79, -0.42]

C(time)[T.17] -0.69, 94% HDI [-0.87, -0.5]

C(time)[T.18] 0.55, 94% HDI [0.37, 0.73]

C(time)[T.19] -0.55, 94% HDI [-0.73, -0.37]

y_hat_sigma 0.31, 94% HDI [0.29, 0.33]

Effect Summary#

Get a prose summary of the causal effects. The summary includes the average post-treatment effect, and if pre-treatment placebo effects are available, it reports on whether the parallel trends assumption appears to be satisfied:

effect_summary = result.effect_summary()

print(effect_summary.text)

Staggered DiD analysis: The average post-treatment effect across event-times was 2.31 (average 94% HDI [2.19, 2.44]). Pre-treatment placebo check: Average pre-treatment effect was -0.01, consistent with parallel trends assumption. Analysis includes 3 treatment cohort(s).

Pre-Treatment Placebo Check#

The att_event_time_ table includes pre-treatment event times (negative values). These represent the average residuals (observed - predicted) for eventually-treated units before they receive treatment.

Important

Pre-treatment estimates are not ATT (Average Treatment effect on the Treated). They are placebo/fit diagnostics that validate the counterfactual model and parallel trends assumption. If these values are close to zero, it suggests the model fits well and parallel trends is plausible.

# Separate pre- and post-treatment effects

att_et = result.att_event_time_

pre_treatment = att_et[att_et["event_time"] < 0]

post_treatment = att_et[att_et["event_time"] >= 0]

print("Pre-treatment (placebo) effects:")

print(f" Mean: {pre_treatment['att'].mean():.3f}")

print(f" Should be close to zero if parallel trends holds")

print()

print("Post-treatment effects:")

print(f" Mean: {post_treatment['att'].mean():.3f}")

print(f" True average effect: {np.mean(list(TRUE_EFFECTS.values())):.3f}")

Pre-treatment (placebo) effects:

Mean: -0.009

Should be close to zero if parallel trends holds

Post-treatment effects:

Mean: 2.313

True average effect: 1.750

Examine the Event-Time ATT Table#

The att_event_time_ attribute provides direct access to the underlying event-time ATT estimates as a pandas DataFrame. This is the same data visualized in the event-study plot, but in tabular form.

When to use this table:

Reporting precise estimates: When you need exact point estimates and credible intervals for a paper or presentation, rather than reading approximate values from a plot.

Custom analysis: When you want to perform additional calculations on the estimates, such as computing cumulative effects, testing specific hypotheses, or comparing effects at particular event-times.

Debugging and validation: When checking that the model is behaving as expected, or comparing estimates across different model specifications.

Exporting results: When you need to save estimates to a file or integrate them into a larger analysis pipeline.

The table includes event_time (periods relative to treatment), type (placebo vs ATT), point estimates (att), credible/confidence intervals, and n_obs (sample size at each event-time).

result.att_event_time_

| event_time | att | att_lower | att_upper | n_obs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | -15 | -0.089727 | -0.182651 | 0.001678 | 12 |

| 1 | -14 | -0.076510 | -0.165531 | 0.015464 | 12 |

| 2 | -13 | -0.117002 | -0.208039 | -0.026421 | 12 |

| 3 | -12 | 0.030745 | -0.059782 | 0.121330 | 12 |

| 4 | -11 | 0.074539 | -0.016959 | 0.164344 | 12 |

| 5 | -10 | -0.076136 | -0.143237 | -0.012652 | 24 |

| 6 | -9 | 0.081386 | 0.014587 | 0.148938 | 24 |

| 7 | -8 | -0.013679 | -0.080336 | 0.051946 | 24 |

| 8 | -7 | -0.032442 | -0.098791 | 0.033575 | 24 |

| 9 | -6 | 0.004729 | -0.060527 | 0.071197 | 24 |

| 10 | -5 | 0.021254 | -0.042810 | 0.082547 | 36 |

| 11 | -4 | 0.018158 | -0.044094 | 0.081336 | 36 |

| 12 | -3 | 0.051156 | -0.011460 | 0.112558 | 36 |

| 13 | -2 | 0.024409 | -0.037726 | 0.085558 | 36 |

| 14 | -1 | -0.033889 | -0.096769 | 0.030393 | 36 |

| 15 | 0 | 1.074842 | 0.990362 | 1.159714 | 36 |

| 16 | 1 | 1.477406 | 1.395102 | 1.559364 | 36 |

| 17 | 2 | 1.936514 | 1.854290 | 2.016924 | 36 |

| 18 | 3 | 2.491325 | 2.412439 | 2.572188 | 36 |

| 19 | 4 | 2.494277 | 2.412555 | 2.577045 | 36 |

| 20 | 5 | 2.439444 | 2.327826 | 2.554720 | 24 |

| 21 | 6 | 2.508034 | 2.391311 | 2.625448 | 24 |

| 22 | 7 | 2.495111 | 2.382095 | 2.607191 | 24 |

| 23 | 8 | 2.554547 | 2.444958 | 2.666289 | 24 |

| 24 | 9 | 2.504438 | 2.390342 | 2.620304 | 24 |

| 25 | 10 | 2.699058 | 2.515626 | 2.879858 | 12 |

| 26 | 11 | 2.379267 | 2.192838 | 2.562129 | 12 |

| 27 | 12 | 2.441211 | 2.260847 | 2.617471 | 12 |

| 28 | 13 | 2.580254 | 2.405220 | 2.759980 | 12 |

| 29 | 14 | 2.625220 | 2.452779 | 2.803349 | 12 |

Group-Time ATT Table#

The att_group_time_ attribute provides the most granular level of treatment effect estimates: effects for each combination of treatment cohort (G) and calendar time (t). This is the “building block” data from which event-time effects are aggregated.

Understanding the difference from event-time effects:

Event-time ATT (

att_event_time_): Aggregates effects across cohorts at the same relative time since treatment (e.g., “effect 2 periods after treatment” averages over all cohorts).Group-time ATT (

att_group_time_): Keeps cohort and calendar time separate, showing effects for specific cohort-time pairs (e.g., “effect for cohort treated at t=5, observed at t=7”).

When to use this table:

Cohort heterogeneity analysis: When you suspect treatment effects differ across cohorts (e.g., early adopters vs late adopters respond differently to treatment).

Calendar time effects: When you want to check if treatment effects vary with calendar time, not just time since treatment (e.g., macroeconomic conditions may amplify or dampen effects).

Diagnostics: When event-time effects look suspicious and you want to trace the issue back to specific cohort-time combinations.

Custom aggregation: When you want to compute alternative summary measures (e.g., cohort-specific average effects, or effects weighted by cohort size).

The table includes cohort (treatment time G), time (calendar time t), and treatment effect estimates with uncertainty intervals:

result.att_group_time_.head(20)

| cohort | time | att | att_lower | att_upper | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 5.0 | 5 | 1.105831 | 0.981070 | 1.234096 |

| 1 | 5.0 | 6 | 1.313366 | 1.191865 | 1.438411 |

| 2 | 5.0 | 7 | 1.874254 | 1.738034 | 2.002803 |

| 3 | 5.0 | 8 | 2.324531 | 2.195446 | 2.449806 |

| 4 | 5.0 | 9 | 2.495319 | 2.365605 | 2.621871 |

| 5 | 5.0 | 10 | 2.330355 | 2.188604 | 2.468263 |

| 6 | 5.0 | 11 | 2.469498 | 2.326770 | 2.611914 |

| 7 | 5.0 | 12 | 2.452538 | 2.311010 | 2.599357 |

| 8 | 5.0 | 13 | 2.521460 | 2.381104 | 2.661465 |

| 9 | 5.0 | 14 | 2.492747 | 2.348853 | 2.636524 |

| 10 | 5.0 | 15 | 2.699058 | 2.515626 | 2.879858 |

| 11 | 5.0 | 16 | 2.379267 | 2.192838 | 2.562129 |

| 12 | 5.0 | 17 | 2.441211 | 2.260847 | 2.617471 |

| 13 | 5.0 | 18 | 2.580254 | 2.405220 | 2.759980 |

| 14 | 5.0 | 19 | 2.625220 | 2.452779 | 2.803349 |

| 15 | 10.0 | 10 | 0.995009 | 0.864157 | 1.123532 |

| 16 | 10.0 | 11 | 1.493974 | 1.367916 | 1.621203 |

| 17 | 10.0 | 12 | 1.948346 | 1.815420 | 2.081204 |

| 18 | 10.0 | 13 | 2.485107 | 2.350294 | 2.616990 |

| 19 | 10.0 | 14 | 2.378103 | 2.246150 | 2.507052 |

Using scikit-learn Models#

For faster analysis, you can use scikit-learn models instead of PyMC. The error bars represent approximate 95% confidence intervals (±1.96 standard errors).

from sklearn.linear_model import LinearRegression

result_ols = cp.StaggeredDifferenceInDifferences(

df,

formula="y ~ 1 + C(unit) + C(time)",

unit_variable_name="unit",

time_variable_name="time",

treated_variable_name="treated",

treatment_time_variable_name="treatment_time",

model=LinearRegression(),

)

# Plot the event-study results

fig, ax = result_ols.plot()

plt.show()

The OLS approach produces similar point estimates to the Bayesian model but runs much faster. However, the uncertainty quantification differs: OLS uses asymptotic standard errors while PyMC provides full posterior distributions.

Key Takeaways#

Staggered adoption requires special handling - standard TWFE can produce biased estimates

The imputation approach fits a model on untreated observations and predicts counterfactuals

Event-study curves show dynamic treatment effects and allow for parallel trends checks

Pre-treatment “placebo” estimates (event-time < 0) are not treatment effects—they are fit diagnostics. Values near zero support the parallel trends assumption.

Post-treatment ATT estimates (event-time ≥ 0) are the actual Average Treatment effect on the Treated

CausalPy supports both Bayesian and OLS approaches for flexibility

References#

Andrew Goodman-Bacon. Difference-in-differences with variation in treatment timing. Journal of Econometrics, 225(2):254–277, 2021.

Kirill Borusyak, Xavier Jaravel, and Jann Spiess. Revisiting event-study designs: robust and efficient estimation. Review of Economic Studies, 91(6):3253–3285, 2024.